HOW IS COMPOST MADE: THE SCIENCE OF THE PLANT GRAVEYARD

When plants die, scores of creatures rush in to take advantage of a sudden supply of food.

In the wild, plants fall where they have lived and their decomposition takes place amongst the living. For plants that share their space with human gardeners, upon their deaths, they will probably be removed and interred in the compost heap. No plants live in this plant graveyard, but the production of compost is so important to the health of our gardens, it is vital for a good plants-person to understand what goes on in the average compost heap.

Living organisms break down the material in a compost heap and, for them to thrive, they must have oxygen. Assuming there is a plentiful supply of air in the compost heap, it will always be teeming with life in various forms.

The first life forms to take an interest in dead plant material are the tiny psychrophilic micro-organisms – mainly bacteria. All those sugars and proteins in the newly dead plants allow the psychrophilic micro-organisms to increase rapidly. They eat as much as they can and, recharged with all that energy, they reproduce extremely quickly.

Eventually, their numbers increase to such an extent that they become victims of their own success. This is because they can only survive in cooler temperatures, but if you’ve added a lot of plant material to the heap all at once, their rampant activity causes temperatures in the heap to rise – making it too hot for them to survive.

Eventually, their numbers increase to such an extent that they become victims of their own success. This is because they can only survive in cooler temperatures, but if you’ve added a lot of plant material to the heap all at once, their rampant activity causes temperatures in the heap to rise – making it too hot for them to survive.

Now it is the turn of the mesophilic micro-organisms to pile in. They can survive at slightly higher temperatures than the psychrophilics but they too become so successful at breeding that they increase the temperature to values even they cannot withstand.

When it all gets too hot for the mesophilic organisms, the thermophilic organisms move in. If the increase in temperature is sufficient to support the thermophilics, then you get more rapid decomposition of plant material and, if it gets hot enough for long enough, most seeds, persistent plant roots and plant diseases will be killed off. Encouraged by the heat they love, the thermophilics breed so rapidly they use up most of the available oxygen until, eventually, they die.

After the demise of the thermophilic organisms, the heap begins to cool and the mesophilics can move back in to continue eating the last scraps of plant material. With the amount of available oxygen in shorter supply, their sexual activities are much reduced, they are sluggish and so they don’t create quite so much heat as they initially did.

At this stage, human intervention in the form of turning the heap to make air available again will initiate a repeat of the whole heating up process and the plant material will break down even further and faster.

Eventually, the plant material breaks down so much as to render it no longer of interest to the bacteria and turning the heap doesn’t serve to heat it up. Now the compost is cool enough to allow all manner of creatures to move in and this little plant graveyard becomes, for a time, a whole city of activity.

Fungi become more active as the heap cools down and they begin to finish the decomposition process started by bacteria. Springtails – tiny little insects that jump around much like fleas – are attracted to the heap to feed on fungi, algae and decomposing plant material. Slugs, snails, millipedes and others are attracted to the decomposing plant material as well. Wood lice take advantage of any rotting woody bits and play a part in helping to break these tougher materials down. Worms ingest the organic matter and produce nutrient-rich excretions.

Fungi become more active as the heap cools down and they begin to finish the decomposition process started by bacteria. Springtails – tiny little insects that jump around much like fleas – are attracted to the heap to feed on fungi, algae and decomposing plant material. Slugs, snails, millipedes and others are attracted to the decomposing plant material as well. Wood lice take advantage of any rotting woody bits and play a part in helping to break these tougher materials down. Worms ingest the organic matter and produce nutrient-rich excretions.

Following right behind the creatures that eat the organic matter are their predators. Spiders prey on springtails and other small invertebrates, while centipedes prey on the spiders as well as everything the spiders might eat. Rove beetles and ground beetles are attracted to the slugs and snails. Toads and slow worms may take refuge in the relatively undisturbed safety of a cooling compost heap and, while they’re there, will snack on slugs and snails amongst others.

Once compost has reached a stage where the larger invertebrates are happy to move in, it enters the curing stage where it should remain quite cool for a period of time to allow the final decomposers to do their work. Eventually the pH in the heap settles down closer to neutral and the amount of humus (fully decomposed organic matter) increases. Humus carries a negative charge which is able to attract positively charged nutrients, thus the final stage of composting increases the compost’s ability to hold onto nutrients and renders it suitable for use.

The whole process can take anywhere from six weeks to six months, depending on how often the heap is turned.

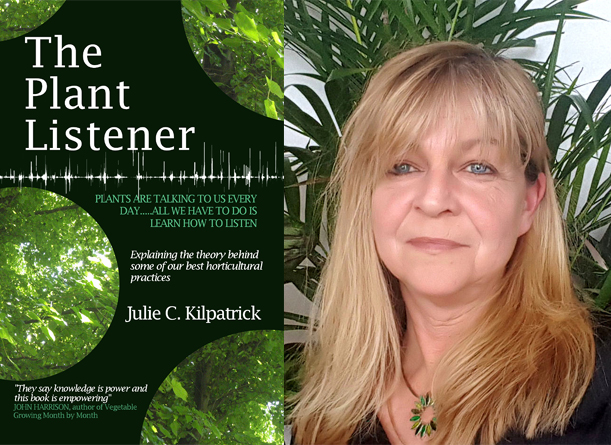

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julie Kilpatrick is a lecturer in horticulture at Glasgow Clyde College, author of The Plant Listener book and editor of gardening website, Gardenzine. For more information see: www.gardenzine.co.uk